Iran, Russia Protests — I Remember 1989. Do You, Vladimir Putin?

If we look closely at revolutions of decades ago, we may see the handwriting on the wall for today’s tyrants

For me, the massive street protests currently roiling Iran — and the parallel disturbances gathering steam in Vladimir Putin’s Russia — bring back memories of the heady days of 1989, when the world changed.

That year, as a newly-minted freelance reporter with no contacts and no guarantee of a home for my articles, I withdrew the last few dollars in my checking account and spent them on trips, first to Berlin, then later to Romania, the scenes of some of the great revolutions of the late 20th century.

Because of what I experienced back then, the protests unfolding now give me the shivers. Yet they also afford us a glimmer of hope, even as, in grim counterpoint, the far-right celebrates fascism’s return to power in Italy and Putin renews threats to lob a nuclear weapon.

***

When we think of “protesters,” a certain archetype suggests itself: mostly young, largely urban, majority male. These are the typical activists we saw in the US during the Vietnam War. That is what you saw in the Arab Spring and the yellow-vest protests in France before the COVID-19 pandemic.

But what I learned on my reportorial forays back then is that protests have an entirely different valence when they are led by women — many of them previously non-politicized — and when they spring up outside urban centers.

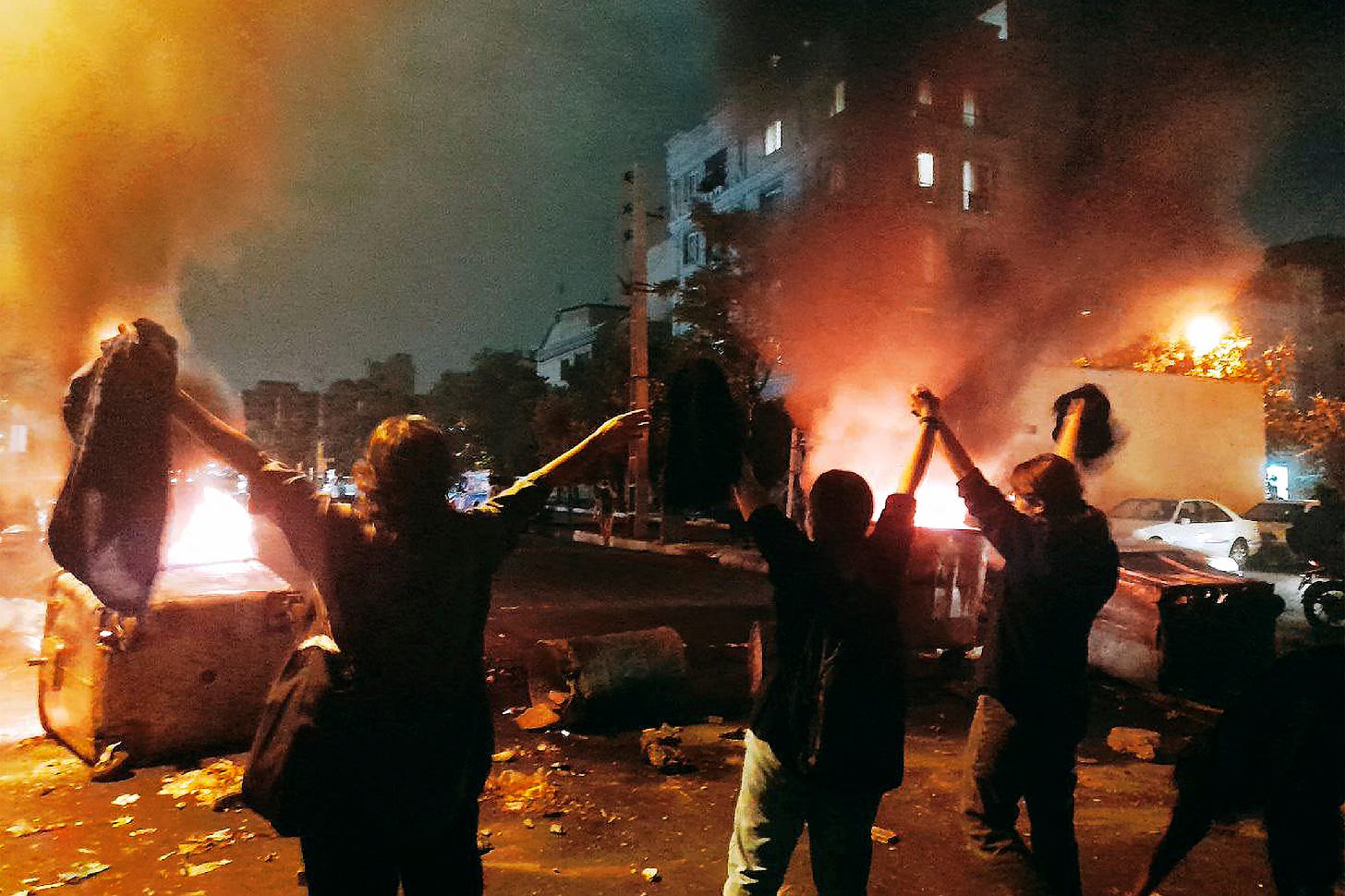

This is the case in Iran, where the killing of a young Kurdish woman — apparently beaten to death over the required wearing of a hijab by the country’s literal “morality police” — has flooded streets all over the country with angry women, pushed to the limit by a crackdown on women’s rights.

As a reporter in Germany and Romania, I witnessed the stirring moment when “ordinary people” saw a chance to assert control over their lives and took it. Now, I feel something similar taking shape in Iran and possibly in Russia — something consequential and, once begun, potentially irreversible.

This is also where I part company with some of my friends, who believe that every pro-democratic uprising abroad — the 2014 Euromaidan protests in Ukraine that toppled pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych, demonstrations against Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela, the “umbrella riot” resistance to China’s repression of Hong Kong — must always be the product of covert operations from a suddenly omnipotent US intelligence.

No, my friends, real people do have feelings and energy and even sometimes agency. The fact that Western countries are cheering this on (and probably helping in any way they can) doesn’t minimize the authenticity of the innate will to freedom.

What’s happened here is that people living under overt tyranny, fully aware they are not free, have reacted out of outrage and self-preservation — in Russia, against Putin’s co-optation of their family members in his “special military operation” in Ukraine — and actually sensed a moment to race for the fences.

The sudden crack in Iran’s autocratic edifice must surely add to Vladimir Putin’s worries. In the Russian heartland itself, the flood of videos documenting resistance to his mobilization of 300,000 soldiers cannot be discounted or ignored. Nor can the flight of thousands and thousands of able-bodied Russians of means to Turkey, Georgia, Finland, and anywhere else they’re safe from being sent to Ukraine with obsolete weaponry and equipment they must purchase themselves.

Remember the autocrat’s age-old nemesis: When masses of “ordinary people” rise up in militant protest, there is no easy recourse. Short of mass murder of their own citizens, in the mode of China’s leaders, a small tear in the fabric of an authoritarian regime can quickly rip the entire garment apart.

***

In late October 1989, as unrest grew in the Communist Eastern Bloc, I, together with a German photographer, tried to cross from West Germany to Soviet-controlled East Germany. The oppressors were still in power, and the East German border guards wanted to know why we wished to come in. We decided to tell the truth. We said we were reporters.

For some reason, perhaps because the border guards had lost confidence in, or fear of, their own leaders, they waved us through.

A while later, as we were taking pictures of a huge plant that processed garbage for West Germany, a couple of state-security policemen in puffy down jackets forced us off the road and demanded to know who we were. My West German friend was pretty fearless, and perhaps a little foolish. To the amazement of the burly Stasi guys, he angrily demanded to know how it was their business, and basically told them to f** off.

I thought this rather risky since they looked like they bludgeoned people for a living. Nonetheless, they paused for a moment, apparently considering their options, then shrugged, climbed back in their car, and drove away.

A bit later, heading deeper into East Germany on a bus, I saw a fellow in a ski mask get on and start distributing leaflets that exhorted the silent but clearly curious and receptive passengers to insurrection.

Related: Russ Baker’s Firsthand Account of the Fall of the Wall

Still later, I was invited to the home of a clergyman who had convened a gathering of his parishioners to get a sense of who was willing to, as it were, make a break for freedom. After some fortifying refreshments, an earnest discussion ensued, during which it became clear that these solid citizens were ready to go forward with something new and uncertain; whatever the risks, they had apparently decided that anything was better than the oppressively regimented life of the hushed conversation, the furtive glance, and the constant fear of a late-night knock at the door.

After the Soviet-built Wall between East and West Germany was torn down (I saved a piece on the spot) I returned to New York. I soon decided that listening to abstract debates about political issues in Greenwich Village bistros could not match witnessing first-hand what oppressed people will do to gain their freedom. Less than two months later, I was back in Eastern Europe, one of many journalists from around the world trying to get into ultra-totalitarian Romania, where, it seemed, about a quarter of the population had been forced into informing on their erstwhile friends and neighbors. (They had to. They knew their leader, Nicolae Ceaușescu, had ordered the killing of more than 60,000 people who had failed to obey their leader’s diktats.)

Related: Hard-Line Police Given Ultimatum

At a border crossing from Hungary, I told a reporter from a Spanish paper I was traveling with, who had tried and failed to gain admission a day earlier, not to worry. She scrunched down in the back seat of my rented car, hoping the armed guards wouldn’t recognize her. To the self-important functionary peering into our car, I explained that we were journalists who wished to enter the country.

He told us that was not possible. “Based on what authority?” I asked. Instead of clubbing us or turning us away, he waved us to the large adjoining building where his higher-ups held court.

With the Spanish reporter trailing me, we entered the building. As we did, I told her I was certain we’d be given permission to cross the frontier. She asked me how I knew. I asked her to tell me what she saw on the wall of the room where we were standing.

“Nothing,” she said. “Exactly,” I replied. “There should be a picture of the dictator, Nicolae Ceaușescu, up there.”

The local guards had already taken it down, and that could mean only one thing: Even the security apparatus of the totalitarian regime had lost confidence in the government.

Indeed, after we made our case to the border chief, he warned us that there was fighting going on and we were taking personal risks to proceed, but that was our business.

We drove overnight on icy roads and managed to survive two potentially fatal accidents. In one mishap we ended up in a ditch, and feared for our lives when two huge figures materialized out of the thick mist. They turned out to be local peasants whose horse and cart towed us back onto the road. All around us, we heard fighting between different military units, some of which had broken away from the regime while others remained loyal — at least for the moment.

Arriving in the capital, Bucharest, we saw men clinging to a facade high above the street, removing the lettering from a Communist Party building. Everywhere long lines were queuing up for… something. At first I thought it must be food or liquor. But no… they were selling newspapers. One man turned around and grinned, one tooth prominently missing, and held up the banner headline for us to see: “Libertate!” (Liberty!)

Related: Celebration and Rage in Bucharest

Thus we were among the first journalists to cover the historic moment when one of the world’s most ruthless and intractable human-control machines sputtered to an end.

Initial resistance involved protests by the Hungarian-speaking minority over the arrest, torture, and banishment of Laszlo Tokes, a dissident clergyman who had boldly delivered sermons criticizing his own church’s cooperation with the murderous regime. Troops had fired on crowds that tried to protect Tokes. Reports that thousands had died outraged people everywhere and ripped off the last veneer of the omnipresent propaganda that had promised Big Brother was benignly looking after you.

Protests grew and spread until the entire country was swept up. Everyone weighed the risks, but once it became clear that key officials would not go along with the regime’s plan to wreak chaos on the country in order to maintain its own power, more and more people began to come out into the streets. Then the army changed sides.

No one was entirely sure what triggered the turning point. Ceaușescu and his even-more-hated wife, Elena, had disappeared to parts unknown. Snipers of allegedly foreign origin (believed to be hired mercenaries) were firing around my hotel, apparently to create panic, prevent crowds from gathering, and dissuade people still on the fence from joining the dash for the finish line.

Meanwhile, in a society where paranoia had become essential to survival and the common answer to the question “Who do you trust?” was “My sister — maybe,” suddenly everyone was talking.

This uncle had been “disappeared.” This cousin had been taken away for “re-education.” That grandchild had been dutifully informing on his parents. One woman told me that her father had worked for the secret police, and that, as he was due to retire, his chair had been irradiated, and he died not long after of metastasizing cancer. She said that was a favored “retirement benefit policy,” since it reduced the government’s pension outlays.

I have no idea if it was true. But everyone had similar stories.

I hired a translator in Bucharest, a melancholy young student who grew more lively day by day. When I gave him money to buy groceries, he returned from the market delighted with a bag of gnarly apples. “There are rumors of oranges,” he told me, “but I don’t believe it.” Still, , like so many of his compatriots, he was already making plans for a new life.

Bearing witness to this transformative experience changed me forever. These memories still bring tears to my eyes.

***

Here’s the lesson that’s most relevant to today: Once certain things start happening, it’s hard to get the genie back in the bottle.

The security forces are the last to go… especially those that are well paid. In Russia, police are comparatively well off, so they would hesitate to sacrifice their enviable standard of living. Now Putin is promising those going into military service (temporary) pay at five times the average national salary.

But, at some point, pressure from families and neighbors and the unofficial grapevine reaches a kind of critical mass — and the end may come with unanticipated dispatch.

In Bucharest, the snipers began to fall silent, and people began edging back into the streets, slowly at first but then with an almost tidal urgency. My hotel pressed me to settle my already huge international phone bill.

On Christmas Day, 1989, I was dozing off while monitoring Romanian TV, when I saw something on the screen I didn’t understand at first: a weeping man and woman held prisoner at a military base outside Bucharest and begging for their lives.

Of course, it was Nicolae and Elena Ceaușescu, for over two decades the all-powerful rulers of Romania, hauled before a summary trial, followed by images of their bodies lying in a courtyard where a firing squad had executed them.

I’m just saying.