Was a “Stop the Steal” Election Hijacking Strategy Brewed Up in Coffee County?

A team of Trump 2020 partisans meddled with voting software to see if they could find proof for “Stop the Steal” claims. Perversely, their “probe” hints at how a future steal might work.

Hello, friends. Here’s the second installment of my new Substack newsletter. I hope you like it. You can subscribe below.

As a subscriber, you’ll enjoy early access to my work before it’s posted at WhoWhatWhy. You’ll also enjoy exclusive Substack-only content.

Today, I’m covering a technical matter. I understand with all the things going on in the world competing for our attention that our default reaction is to skip anything arcane and complicated. That’s a mistake. The world IS complicated, and if we don't take time to figure things out, who will? You may not like the answer.

************************************************************

Secret Service Flaws and Failures Are Nothing New

The U.S. Secret Service has determined it has no new texts to provide Congress relevant to its Jan. 6 investigation, and that any other texts its agents exchanged around the time of the 2021 attack on the Capitol were purged, according to a senior official briefed on the matter. — The Washington Post

I gotta say, all this bewilderment and frustration with the Secret Service for destroying and “losing” crucial text messages from January 6 is driving me crazy.

How about caring more generally about the Secret Service, its overall accountability, and its functionality in service of the public interest — and how on all of the above, it has a history of failure, ineptitude, and worse?

Most media (and most polite company) prefer not to talk about the assassination of John F. Kennedy (“conspiracy theories — ugh”) but try this on for size:

When a Black Secret Service agent on the White House detail tried to blow the whistle on both the agency’s rampant racism as well as its shocking security lapses that threatened Kennedy’s safety, the Secret Service drummed him out of the detail, framed him for a crime he didn’t commit, and then put him into a mental asylum.

On November 22, 1963, the Secret Service actually pulled agents off of Kennedy’s car, then later falsely claimed that was the president’s wish. This eliminated a critical protective layer and helped ensure Kennedy was a goner.

The Service also destroyed records before 2021: In 1995, when the governmental Assassination Records Review Board requested relevant documents, the Secret Service replied that it had just destroyed “presidential protection survey reports for some of President Kennedy’s trips in the fall of 1963.”

Of course, some of you may remember all the scandals in the years between then and now, with Secret Service agents being drunk, missing from duty, and consorting with prostitutes while on official trips, on and on.

Others involve embarrassing and dangerous failures in the protection of former President Barack Obama, one of which involved a man who got into the White House. But one of the strangest incidents occurred in Australia, when a reporter found, lying in a gutter, a booklet containing highly sensitive information concerning security arrangements of the trip.

I’d love to hear what you think about the job our elected officials are doing to make sure we have a fine and responsive protective force. As for me, I think Vice President Mike Pence knew exactly what he was doing when he refused to get into that armored car when the Secret Service told him to do so.

TODAY’S FEATURE:

How Coffee County Might Reveal ‘Stop the Steal’ Election Hijacking Strategy

Republican activists, operatives, and partisan officials organized under the “Stop the Steal” rallying cry — whether sincerely believing that the 2020 election was stolen or cynically trying to collect dubious “evidence” to convince others it was — have been deployed all over the country since Donald Trump lost the White House to Joe Biden, digging for proof that voting was subject to manipulation and rigging.

One such effort, in a rural Georgia county with just 25,000 voters, could have profound consequences for the rest of the country. And it just might provide crucial clues on what is needed to fix our democratic system and restore confidence in election results.

***

On the afternoon of January 6, as a mob egged on by Trump stormed the Capitol in Washington to disrupt Congress’s certification of the presidential election, an Atlanta man set in motion final details for an inspection of the elections department computer system in rural Coffee County, GA. (The narrative details below are partially based on text messages provided to The Washington Post and The Daily Beast — and are summarized and interpreted by me.)

A purportedly expert forensic team was assembled by Scott Hall, an Atlanta bail bondsman whose Facebook page boasts photos of him with Donald Trump, Donald Trump Jr., Sean Hannity, Tucker Carlson, and other stars in the right-wing firmament.

But the idea may not have been Hall’s, or Team Trump’s. It may have been locally brewed — in Coffee County.

Shortly after the 2020 election, Emily “Misty” Martin, then-Coffee County elections supervisor (she later would be known as Misty Hampton), made a video that claimed to show how election results could easily be altered by someone with access to the computer server running Dominion software.

Someone with ill intent could manipulate the results by scanning the same ballots twice, changing voting preferences, and other methods of tampering. An observer can be seen and heard on the video saying, “I don’t know why they approved such a system — I don’t get it.”

Martin’s point that the elections software is vulnerable might appear valid to a viewer, since on camera she appears to successfully alter ballots — though she doesn’t seem to know exactly how the software works or whether the altered ballots were actually counted.

Furthermore, critics of Martin’s analysis noted, each challenged ballot in every county in Georgia — and in most places nationwide — is reviewed by a politically balanced trio that includes a Republican, a Democrat, and a third person appointed by the election authorities.

Still, even though these revelations were made after rather than during the election, the very fact that Martin was able to access ballots without the mandated oversight personnel present raised questions about just how secure the system is.

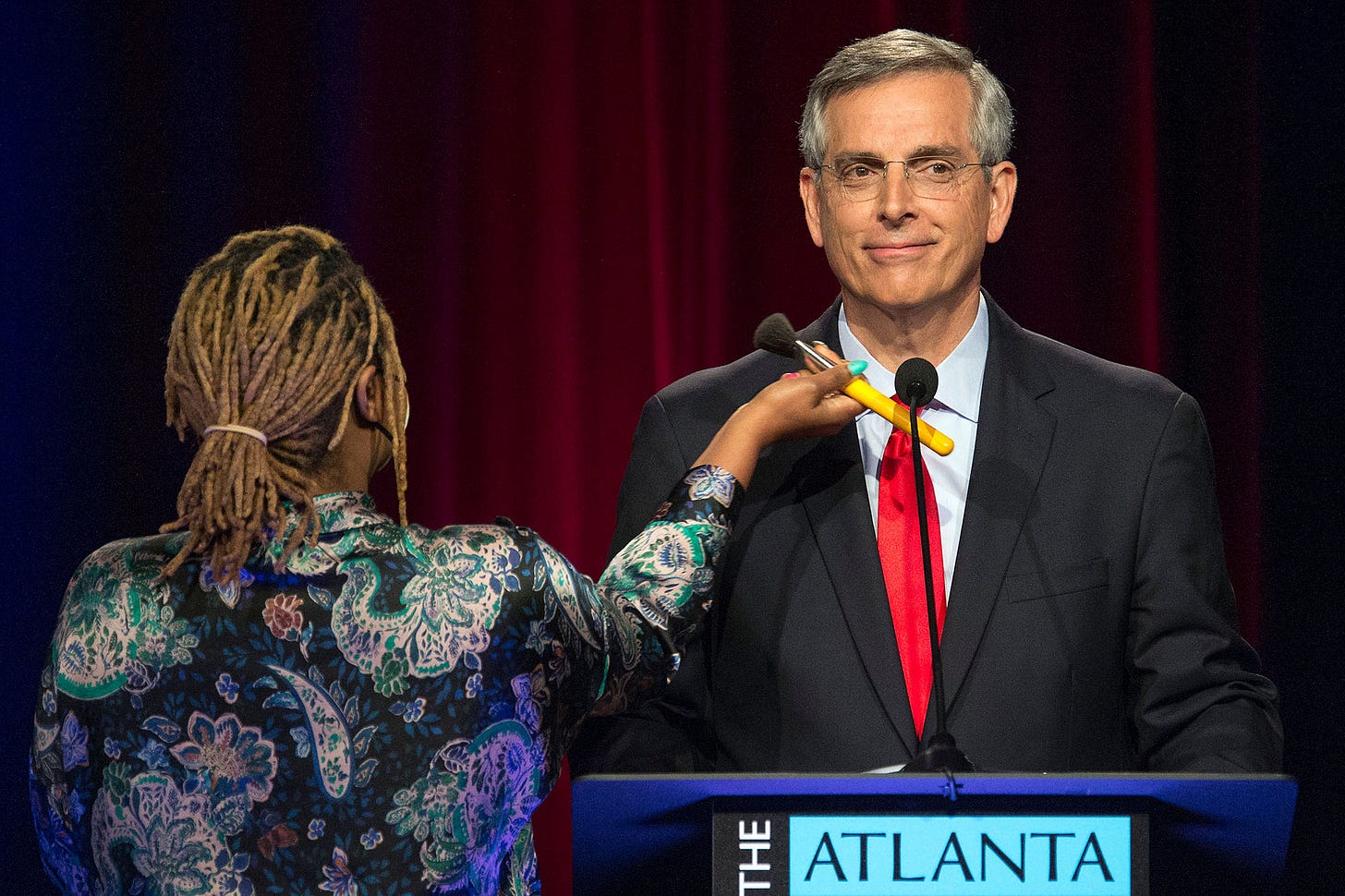

Martin made the video after a series of Election Day glitches — and the Coffee County Board of Elections and Registration’s lone refusal, among all Georgia counties, to certify its final vote count by an early-December 2020 deadline triggered an investigation from Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger (R). (Raffensperger himself testified before a Fulton County grand jury in a separate investigation launched after Donald Trump’s infamous directive to Raffensperger to “find votes.”)

At one point, Martin conceded that the 50-vote discrepancy she seized upon could have been her own error — the result of her accidental scanning of one batch of ballots twice. Ultimately, she was forced to resign, with the stated reason that she and a co-worker falsified timesheets.

Her early-December 2020 video, which was widely circulated among Trump partisans, fed beliefs that something was amiss with the entire presidential election. The claim dovetailed with a broad effort — instigated by Trump himself on election night and later seized upon by Trump campaign attorneys Sidney Powell and Rudy Giuliani — to raise public doubts about the vote’s veracity and file lawsuits challenging results (but only results that went for Joe Biden).

Getting Access to the Code

A few weeks later, in early January 2021 -- as confirmed by a text from Martin to Eric Chaney, one of the five Coffee County elections commissioners who hired her -- Hall (the Atlanta bail bondsman) expressed his interest in bringing in an outside team to investigate Coffee County. He spoke to Cathy Latham, who was at the time Coffee County’s Republican Party chair:

Scott Hall is on the phone with Cathy about wanting to come scan our ballots from the general election like we talked about the other day. I am going to call you in a few.

With Latham’s consent, Hall chartered a single-prop plane that flew into Douglas Municipal Gene Chambers Airport the next morning.

Coffee County GOP officials excitedly texted each other the details as the operation was underway.

“Team left Atlanta at 8… 5 members led by Paul Maggio… Scott is flying in,” Latham texted on January 7 at 9:46 a.m.

Maggio is an executive at an Atlanta-based computer forensics and data storage company. He and his firm, Sullivan Strickler, had recently served as hired expert witnesses in a lawsuit filed by a local resident against Antrim County, MI, alleging vote tampering. They took “forensic images” of the voting system.

The text messages show that the team included Jeffrey Lenberg, a retired Sandia National Laboratories engineer described by Trump-friendly media as a “systems vulnerability expert.” He had worked with Maggio on the Antrim County computer systems review and was involved in audits of voting in his home state of New Mexico.

The five-person “forensic” team headed straight to the windowless Elections and Registration building, where they were joined by Latham and Chaney.

With access granted by the local officials, they were able to make a copy of the operating software on a computer server containing the elections management system — a system used throughout the state.

What Can Be Done With Such a Code

Although we don’t know whether they found anything amiss, the very fact that they have access to the code makes it at least theoretically possible for them — or others — to alter that code and thereby compromise voting in the state.

In addition, their being able to breach the system left digital “breadcrumbs” that later could be cited as a basis for questioning whether the system was, or could be, breached.

All this could in turn be used to raise doubts about an election outcome in November or in 2024.

Paradoxically, Raffensperger, Georgia’s Republican elected secretary of state, has a stake in suppressing the details of the break-in and continuing to insist that the system is inviolable — making him an (unlikely) fellow traveler with Democrats who want everyone to trust the results in 2020 and beyond.

The problem is, if those GOP partisans who have access to the code were to use it to alter the system, Raffensperger would be there — with his new popularity and credibility with the Democrats and media — to reassure us that we can trust the count.

This obviously matters greatly when the balance of power in the US Senate (and hence in the country) could be decided by the outcome of Georgia’s November Senate election. In that race, freshman Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock is facing a challenge from Trump-endorsed Herschel Walker, the retired professional football player. Meanwhile, this year’s gubernatorial race could determine control of the Georgia voting machines and system for the 2024 presidential election.

The stakes in Georgia are extra high for the country both because they involve national-impact electoral battles and because Georgia uses a voting system that academic experts consider especially flawed and susceptible to hacking. (In the near future, I’ll try to look at the particulars of the software, from Dominion, and compare it with other systems used elsewhere, some of which have their own profound flaws. For now, I’ll just note that Dominion’s software is principally intended to assist disabled voters; Georgia is the only state using it statewide for all voters.)

Raffensperger has not denied the susceptibility, but said it is not a problem because only authorized personnel have access. The Coffee County incident proves that a single “authorized” person could gain access and share that access with an outsider.

Raffensperger’s Dubious “Good Guy” Status

Brad Raffensperger is supposed to be the good guy in Georgia because, though a Republican, he refused Donald Trump’s directive to “find” just enough votes to win Trump the state, bucked the Stop the Steal movement, and said the election results in 2020 were credible. He faced their wrath and became an unlikely hero in the mainstream media, and to Democrats nationwide.

However, the incident in which GOP-affiliated technology experts had secret, unauthorized access to the state’s all-computerized voting system shows that Republicans could turn the situation around, alter the results, and then find shelter in the Democrats’ prior claim that the system is secure. Of course, agnostically speaking, anyone of any party could do the same.

(1) Their own access created a perception that the system is not secure (thereby undermining trust in the system); and (2) as noted, their access to the system and the software could be exploited to alter actual results.

So far, Raffensperger’s office has not revealed any meaningful results from his Coffee County investigation. This has led to a complaint filed by election integrity activists. Although the complaint doesn’t say so, it’s possible to read between the lines and conclude that, politically, Raffensperger has a strong disincentive to fix the problem, and that this inaction could open the way to manipulation of the upcoming midterm election in the state.

The breached Coffee County elections computer was subsequently removed by state officials, but no chain of custody exists for the computer, and the vital evidence it contains — of tampering with its basic software code — is currently out of sight. The complaint asks: “Did the Secretary’s staff illegally remove the only electronic copies of the county election records without a court order or other authority?”

Does Cyber Ninja = Trojan Horse?

Ostensibly, the team that got unauthorized access to the Coffee County server was looking for evidence of vote tampering, based on a disparity of 50 votes between the count and a recount. However, that disparity was far too small to alter the 2020 outcome in the state, though if one viewed any such disparities as “iceberg tips,” the case could be made that extrapolating them statewide might be outcome-altering.

Still, the very fact that the team got access for its purported inquiry could potentially have served as a two-bellied trojan horse: (1) Their own access created a perception that the system is not secure (thereby undermining trust in the system), and (2) as noted, their access to the system and the software could be exploited to alter actual results anywhere such a system is in use.

All of this, including the state’s strange lack of transparency in its investigation and its seizure and sequestration of the computer, could serve to raise already, high levels of suspicion.

Lurking in the background is the fact that experts have long considered Georgia’s system risky. The reasons for this may be too technical for most readers’ taste. But simplifying, it is believed that unscrupulous parties could engineer an end-run of the “paper trail” so that the system would appear to confirm that votes were counted properly, when in fact they might not have been.

Because of these vulnerabilities, we end up with a situation where the Stop the Steal crowd could, perversely, claim to be right — albeit for the wrong reason.

Ironically, it was mostly a small number of politically liberal activists who, starting years ago, warned that computerized voting without strong paper trails, audits, and safeguards, was risking the country’s voting infrastructure. Those activists — whose complaints were covered extensively by this news organization years ago — were largely ignored by the Democratic establishment. (To see a sample selection of these stories, please go here.)

So the Democrats find themselves in a pickle, at least in part of their own producing: Their reflex reaction to Stop the Steal has led them to assure voters that the voting system is perfectly secure — when it’s not. Paradoxically, this gives very unintended cover to their seemingly more strategic political enemies, should they decide to exploit the system’s unaddressed vulnerabilities and manipulate the voting process for their own illegitimate gain. It’s all part of the weaponization of election forensics and election “integrity,” and it is a profoundly dangerous game.

WhoWhatWhy and I intend to keep on this story. Stay tuned for updates and new reporting.